Friday was the 81st anniversary of the Allied landings at Normandy, France—the largest amphibious military invasion in history. The operation marked the beginning of the end for Nazi Germany, as Allied forces began to liberate Europe from occupation.

I took the above picture when I had the opportunity to visit that hallowed ground in 2018. Here is my favorite essay about D-day, and just how close to failure the Omaha landing was.

I taught ROTC at a University before I retired from the military, and I used to give the essay to my Midshipmen to highlight of the importance of tactical level leadership. One of the wild things about military service is, just like Forrest Gump’s chocolates, you never know what you will get. You could go an entire career and never have anything eventful happen (not likely but technically possible). Or you could do one four year tour and be present at a hinge point, where a battle turns. Maybe it changes the momentum of a campaign, and alters the course of a war.

From Ken Nightingale’s essay:

At approximately 0830, 6 June 1944, Omaha Beach was virtually lost to the Allies. Disaster stretched across the 3 plus miles of beach. Bodies piled from horizon to horizon. None of the extensive fire support was either effective or even applied due to weather and smoke. Units ceased to exist as the ramps dropped on the hundreds of landing craft. Not a single command radio functioned on the beach, robbing the commanders afloat of the ability to render sound decisions. Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley, the overall commander, began to formulate plans to withdraw from the beach and land behind the British at Juno. He and the remainder of the force, were saved by several junior officers and NCOs who disobeyed orders with studied judgment. They realized that disobeying clear orders was a necessity for success where adherence would underwrite defeat.

It’s a great example of the difference between linearity and nonlinearity, of how a few actions can aggregate together into something greater than the sum of their parts.

Some things can be optimized, made more efficient. These are linear processes—we can follow a formula or a recipe and scale something up.

The trouble is, most things humans are involved in—and war is a great example of this—are nonlinear.

Linearity and Nonlinearity

Linear things are amazing. Linear processes can be reliably scaled and are responsible for much of the wonders of the modern world. But linearity isn’t the only thing going on. The nonlinear is afoot as well. It’s the stuff of virality, of the whole being greater than the sum of its parts—like the combination of

Sometimes the friction and the conflict are the point—the place where the magical or terrifying emerges from an unknowable mixture of factors, inputs, and circumstances.

Like a toddler shoving a square peg into a round hole, humans try to shoehorn the nonlinear into the linear. This results in a Bed of Procrustes-type situation, where long things are chopped down and short things are stretched beyond recognition.

This represents the McGilchristian Left Hemisphere in action—seeking to minimize novelty, strip out nuance, and hollow out experience, all in favor of a soulless, mechanized outcome. Large Language Models pour gasoline on this dumpster fire already in progress.

We still need humans, with the resilience to deal with adversity, the discernment to suss out the signal from the noise, and guided by an ethos that prioritizes both individual virtue and the flourishing of the collective.

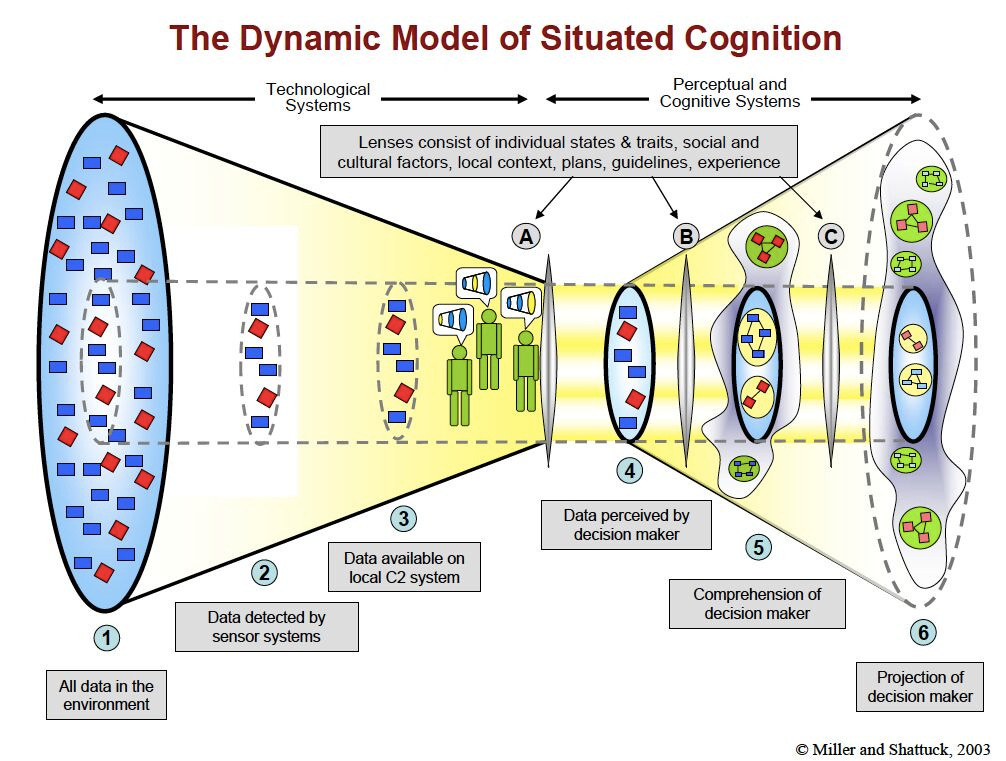

The essay brings up the tactical truism that those closest to a situation often have a better understanding of what needs to happen, rather than upper-level leaders and policy-makers, who are separated from ground truth by consecutive layers of sense-making systems that often obscure or confuse their view.

More teasers from the essay:

“This was the pivotal watershed moment of D Day--three Navy officers and four Rangers, disobeyed orders and created the decisive acts of disobedience that saved the beach. As a major in Frederick the Great's German army admonished a lieutenant during a battle:

"The King gave you a commission because he assumed you knew when to disobey an order."

There is a lesson here. Flexibility exercised with good judgment is a pearl without price if it resides within the mind of the man on the spot.”

"Like a toddler shoving a square peg into a round hole, humans try to shoehorn the nonlinear into the linear. This results in a Bed of Procrustes-type situation, where long things are chopped down and short things are stretched beyond recognition."

Excellent analysis, Adam! Jean Piaget studied cognitive development in children. He described 2 core mechanisms: ASSIMILATION (change the world to fit our mental structures) and ACCOMMODATION (change our mental structures to fit the world). When dealing with complexity, we mostly default to OVER-assimilation. Problems follow.

I hated reading Piaget in grad school. As often happens, he turned out to be one of those "hard but brilliant" types. I bet you're running into some of that in your program!

My wife and I visited the beaches in June 1984 — 40 years after the landings. Obviously a shorter trip for us being in the UK but the ferry across from England to France was heaving with US former service personnel and their families. For some it was the first time back and clearly very moving — especially remembering lost comrades.

I fully agree that those on the front lines, in military or civilian endeavours, invariably do the richest sense making. Unfortunately that’s almost always disconnected from decision-making by the high ups so that when those decisions eventually work their way back to the front line, invariably they don’t make sense.